Rewiring recovery: Inside the quest to understand how the brain rewires itself after stroke

Article | December 5, 2025

Every year in the United States, nearly 800,000 people suffer from a stroke. For survivors, post-stroke symptoms can be devastating. Weakness or paralysis on one side of the body, balance and coordination problems, difficulties with speech, loss of vision, and trouble swallowing can plague stroke survivors for years, or even the rest of their lives.

In her lab at JAX, Assistant Professor Mary Teena Joy is studying exactly how the brain’s neural circuits change after a stroke—and the effects that has on stroke survivors. She hopes to identify precise, targeted therapies that could help restore some of the loss of function stroke survivors face every day.

“We’ve gotten better at survival rates from stroke, but now people are living with long-term deficits,” said Joy. “There’s a real need for new therapies that can treat patients after a stroke.”

Paths of neuroplasticity

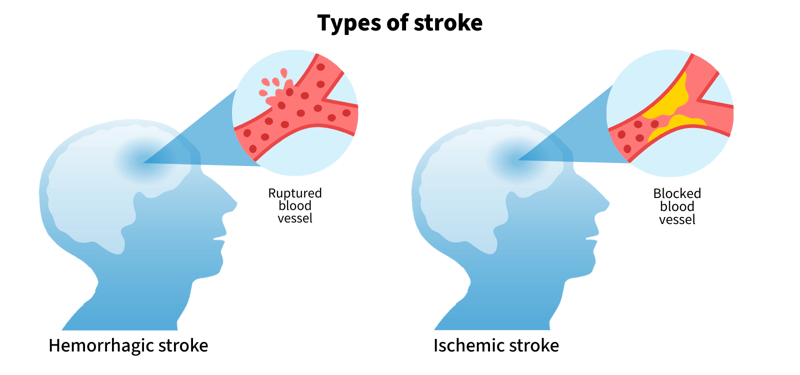

The researchers in the Joy Lab primarily study ischemic strokes, because they’re the most common. When a person has a stroke, the blood supply is cut to a portion of their brain. The tissue in that section dies — a permanent loss that can never be repaired back to its original function. But the brain is a remarkable organ, and while it can’t replace the injured portions, it can adapt to new injuries, an ability known as “plasticity.”

Brain plasticity is the brain’s ability to change and reorganize itself throughout life. These are structural and functional changes in the brain, including forming new neural connections in response to experiences, learning, and environmental stimuli. Humans experience the most brain plasticity before they reach adulthood, but after a brain injury like a stroke, there’s a window of plasticity where the brain restructures itself to account for the injury.

The trouble is not all plasticity is positive and sometimes lost tissue forces the surviving brain circuits to rewire in ways that can hinder a patient’s recovery.

“All the neurons in the brain are highly interconnected. When you lose a core set of neurons, it affects all the other regions because they’ve lost their partners,” said Joy. “We’re trying to understand what the roadblocks are. What are the mechanisms that stand in the way of complete recovery?”

Think of it almost like a sinkhole in a busy town, where the neuronal pathways are the existing roads. After a stroke, there is an entire area in the brain that functionally no longer exists. But much like after a sinkhole, people (or neurons) still need to get from point A to point B. Detours and new routes are made to get around the new obstruction. But there are lots of possible configurations for those new paths to take.

“Every stroke patient has a very unique path of recovery,” said Michael Alasoadura, a postdoctoral researcher in the Joy Lab. “We like to say: ‘Every road leads to Rome, but the paths are different.’”

Better understanding each of those paths to recovery will lead to better therapies for each patient, he added.

Reach, grab, handle, and pull

To help understand the changes in the brain behind loss of motor control, one of the most common symptoms of stroke, the researchers in the Joy Lab brought in four-legged lab assistants.

Using a specially-designed rig, the mice are trained to do two different tasks—reach, grab, handle and string pull. For the reach, grab, handle task, the mice are trained to reach for a piece of pasta, break it, and retrieve it.

“The grasping and handling movements they use actually model human dexterity really well,” said Joy.

There is also a string-pulling task. The mice pull three feet or so of string, hand over hand, to get to a peanut butter-covered Cheerio. This represents bimanual tasks stroke victims can struggle with such as tying shoelaces or buttoning up a shirt. Kiley Martin, a predoctoral associate in the Joy Lab, is leading the string-pull experiments. Martin is earning a Ph.D. in Neuroscience through the ‘Neuro at JAX’ track of the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at Tufts University School of Medicine. At JAX, Kiley studies regeneration and functional connectivity in the brain after ischemic strokes and is interested in developing methods to improve outcomes post-injury.

For Alasoadura, building the behavioral rig was one of the coolest parts of the research. “We worked closely with the JAX fabrication team to design and build a system that lets us study dexterity in such detail. Outside of a place like JAX, something like this would be incredibly difficult or even impossible to build,” he said.

The mice are recorded doing their tasks at 500 frames per second before stroke, after stroke, and all through recovery.

“If we can see why a movement or task fails after stroke, we can start to understand what might help it succeed,” said Vyshnavi Sankaran, a research data analyst in the Joy Lab who uses machine learning and AI to analyze the mouse actions.

The team is also using widefield and two-photon mesoscopic imaging, which lights up the areas of the brain where neurons are active. When neurons fire, those signals are captured by a microscope, and they get time-resolved images of brain activity with the resolution of single neurons. That lets the team match exactly which actions the animal is taking with what’s happening in the brain—sometimes down to a few milliseconds.

“We need to understand not just one damaged region, but how the entire brain adapts to that change,” said Joy, who added that with deep learning an AI, they finally have the tools to probe and analyze large-scale neural activity in order to see how all the parts in the brain act together. “Deep learning lets us measure not just whether an animal or a patient can do a task, but how they do it — and it will help us measure the quality of recovery.”

Joy said she hopes that these models could one day improve clinical assessments in stroke recovery, which are often qualitative rather than quantitative.

Targeted therapies

Looking ahead, Joy and colleagues want to translate their discoveries from mice to people, using artificial intelligence to bridge the gap between brain activity, behavior, and recovery. By mapping the neural patterns that support regained movement and identifying the circuits that help (or hinder) healing, the team hopes to one day guide more personalized, effective rehabilitation after stroke.

“The future is going to be personalized medicine — where each person’s recovery plan is tailored to their specific brain and their specific injury,” said Alasoadura. “What we’re doing at JAX right now is laying the groundwork for those kinds of predictive tools,” he said.

The long-term vision is not just to understand how the brain changes after injury, but to help design smarter, faster paths to recovery for patients.

“The next frontier is identifying therapies that work for chronic stroke patients — people who have already survived the initial event,” said Joy. “Our work is about understanding emergent properties of the brain after injury and using that knowledge to design better therapies.

Learn more

The Joy Lab

The Joy Lab is interested in understanding how circuits in the brain rewire after a stroke and other CNS injuries, with the goal of identifying molecular and circuit principles for recovery.

View more

How can stroke recovery be improved?

Mary Teena Joy investigates what happens to the brain after a stroke and how to enhance brain neural rewiring to improve recovery.

View more